In this article, we will learn how to use the fire-and-forget pattern to improve performance of system with its implementations.

Let’s get started.

Table of contents

- The Fire-and-Forget pattern

- Introducing ThreadPoolExecutor

- Implementing Fire-and-Forget using ThreadPoolExecutor

- Introducing ForkJoinPool

- Implementing Fire-and-Forget using ForkJoinPool

- Introducing Threaded Recursion with ForkJoinPool and BlockingQueue

- Implementing Fire-and-Forget using Thread Recursion

- Wrapping up

The Fire-and-Forget pattern

One of the typical benefits of a single-threaded application is ordering. When a process invokes a method, the ensuring lines in that process aren’t run until the invoke method has completed. This natural blocking makes it easier to reason about the state of the process at any given time. It is, of course, expensive.

Consider the scenario where the callee is slow to do its work, but the caller is fast to do its work. Our application pay for this ordering guarantee by slowing the caller down. Indeed, if the caller blocks, then it can never take less time than the callee takes, kind of like being in line at the supermarket, where the caller is standing behind the callee in line. The passing of context back and forth has its costs as well. In the scenario that we are looking at, the originating process doesn’t care about the child process’s outcomes. When we blocks, we obligate the child process to pass context back in the form of a return statement, which is more then we need to do here. The

–> We have piece of information that we need to care about:

-

Operating on a single-thread bounds the application’s performance to the slowest instructions.

-

Anticipating a reply doubles the work that needs to be done.

-

Fire-and-Forget addesses both.

Introducing ThreadPoolExecutor

In this article, we will learn three options to implement the fire-and-forget pattern. Each give us an opportunity to identify important nuances of the problem, and the potential tradeoffs that each approach offers.

- Using

ThreadPoolExecutor. - Using

ForkJoinPool. - Using

Thread Recursion.

The ThreadPoolExecutor is one of many classes that implements the ExecutorService interface.

// each instance an appropriately configured instance of ThreadPoolExecutor

ExecutorService pool = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

ExecutorService pool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(3);

ExecutorService pool = Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor();

The purpose of this interface is to provide an abstraction layer around the management of asynchronous tasks. It addresses several pain points.

-

The first pain point is using threads that they are expensive to spawn. Overtime, responding a new thread for the same task each time we need to perform, it will take as much as four times as long as reusing a single thread to perform the same task over and over.

Thus, what the

ThreadPoolExecutordoes is maintains a pool of threads available for rapid reuse. When a thread allocated by theThreadPoolExecutorcompletes, it holds onto the reference for a specific period of time, during which another submission can be made against the same thread. This saves time, similar in concept to the way that a database connection pool can save time. -

The second pain point is thread API abuse. It’s unsavory to extends a thread in order to make a task concurrent, and it’s flat out incorrect to call the

run()method instead of thestart()method on the thread class. These mistakes are very easy to make and have been the subject of many a code review over the years.Perhaps more importantly though, this abstraction elevates our focus to

runnableandcallable, which are much easier to work with, requiring the developer to commit to less at implementation time, and allowing different layers of the application to reason about the tasks themselves, independent from how or when they will be executed. -

The last pain point is regarding pipelining.

ExecutorServicemakes it easy to reason about results of asynchronous tasks via JavaFutures, something originally unwieldy in the original thread API.Futures can be blocked on, ignored, or delegated to other layers of the application.

-

Note that the instances of

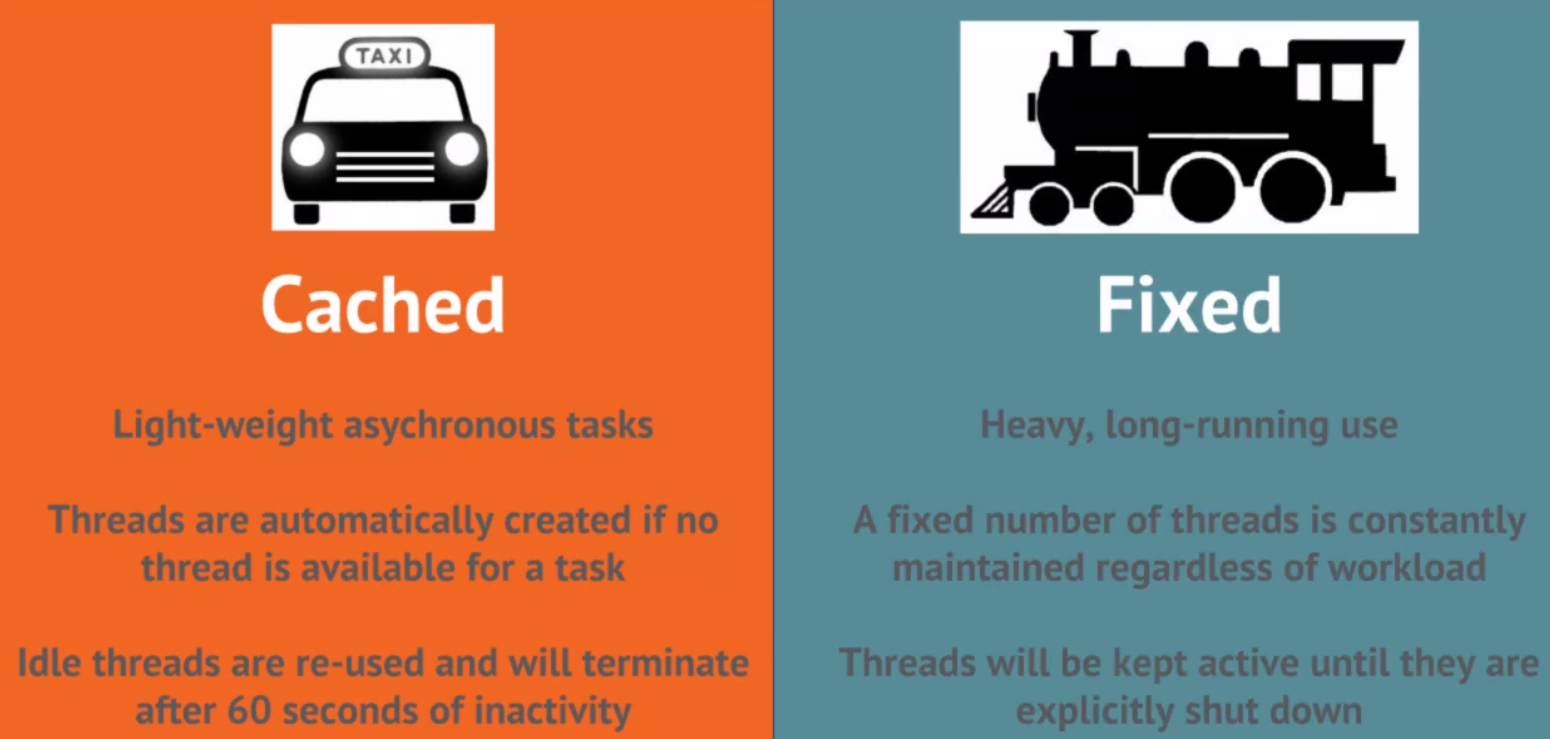

ThreadPoolExecutorcreated via the executor static factory will not block on task submission, even if no threads are currently available. This is because in the background they maintain a queue from which tasks can be plucked as threads do become available.The executor static factory affords coders a lot of options for the kind of thread pool they could construct, but which is better for what situation? Two of the main options are whether to use a cached thread pool or a fixed thread pool.

Using a cached thread thread pool is like commissioning a taxi service. A taxi service is best when there are several ad hoc, short trips, and the pool of resources may need to grow or shrink along with demand. Likewise,

a cache to that pool is helpful for lightweight asynchronous tasks.- When a task is submitted to a cached thread pool, if there is no currently available thread, a new one is spawned immediately.

- Available threads are reused until they sit idle for 60 seconds, at which point the threads are killed and the memory is reallocated.

The train service is different from a taxi service in that the intent is for regular and heavier loads. Trains may operate on a schedule independent from the needs of the consumer, and if a train isn’t currently at the station, consumers will need to wait in line. Likewise, a fixed thread pool is helpful for heavy, long running use. These thread pools begin at a configured size and remain the way until the pool is explicitly shut down, regardless of load. If a thread is available when a task is submitted, the task is added to queue.

Implementing Fire-and-Forget using ThreadPoolExecutor

Let’s look at the following source code:

public class IdentityPipeline {

public void process(InputStream input) {

Identity i;

while ((i = readIdentity(input)) != null) {

final Identity identity = i;

try {

validateAddresses(identity);

phoneNumberFormatter.format(identity);

emailFormatter.format(identity);

if (!identityService.persistOrUpdateBestMatch(identity)) {

statsLedger.recordEntry(new StatsEntry(identity));

}

} catch (Exception e) {

malformed.addIdentity(identity, e.getMessage);

}

}

}

}

With the above code, we will apply the fire-and-forget pattern to send requests to the error queue. The original interface is MalformedIdentityRepository, and an instance of it is invoked at the end of while loop, in catch block.

To keep the code focused on concurrency, the actual implementation of this interface is just a step that waits for a configurable amount of time. In the unit test that executes this code, the wait time for each call to the repository is 1 second in order to make the concurrency gains obvious over very small data sets.

Below we will use ThreadPoolExecutor to implement the fire-and-forget pattern.

public class ThreadPoolExecutorMalformedIdentityRepository implements MalformedIdentityRepository {

private MalformedIdentityRepository delegate;

private ExecutorService pool = Executors.newCachedThreadPool();

public ThreadPoolExecutorMalformedIdentityRepository(MalformedIdentityRepository delegate) {

this.delegate = delegate;

}

@Override

public void addIdentity(Identity identity, String reason) {

// first way

pool.submit(() -> this.delegate.addIdentity(identity, reason));

// second way

new Thread(() -> this.delegate.addIdentity(identity, reason)).start(); // SLOWER

}

@Override

public void addIdentity(InputStream message, String reason) {

pool.submit(() -> this.delegate.addIdentity(message, reason));

}

}

Introducing ForkJoinPool

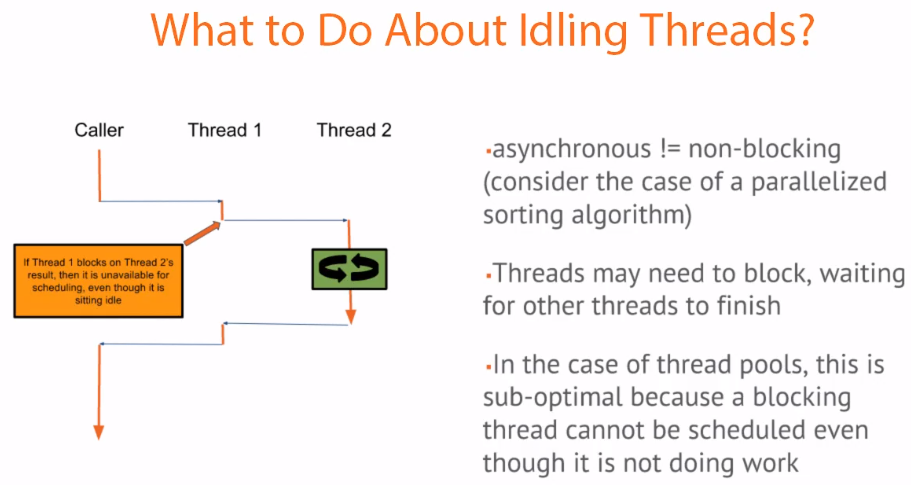

ForkJoinPool is new implementation that was introduced in Java 7 to address the concern of unscheduled idle threads. A common misconception in the threading world is that launching something in a separate thread implies that there’s no blocking happening. Indeed, a parent process may block on the results of an asynchronous tasked launched in some descended process. In this situtation, the thread that is executing the parent process is idle, which is suboptional since technically it could keep itself busy doing other work while it waits.

ForkJoinPool, also known as a work stealing pool, addresses this concern. Some features of ForkJoinPool that we need to know:

-

ForkJoinPool provides the same design and orchestration benefits as ThreadPoolExecutor.

-

What makes this implementation different is that by default threads are daemond threads, meaning that the main execution thread will not wait for them to complete when the JVM shuts down.

-

More importantly though, processes launched via ForkJoinPool may steal work from one another, which is nice for threaded recursion, or any scenario where one thread may be blocked by the execution of another thread and could keep itself busy doing something else in the meantime.

E.g: in the case of Divide and Conquer algorithms.

-

An instance of ForkJoinPool can be obtained in the same way as ThreadPoolExecutor, through the executors static factory. Also, there is a ForkJoinPool that is common across the JVM, this pool is used by the Java Stream API in Java 8. Because the ForkJoinPool is mostly intended for divide and conquer algorithms, if we end up using the ForkJoinPool constructor directly, remember that the Java documentation recommends that the concurrency level is provided in a constructor’s parameter should be a power of two.

// each returns an appropriately configured instance of ForkJoinPool ExecutorService pool = Executors.newWorkStealingPool(); ExecutorService pool = ForkJoinPool.common(); // in pool should be a power of two ExecutorService single = new ForkJoinPool(16);

Implementing Fire-and-Forget using ForkJoinPool

To appy ForkJoinPool, we should come back our problem in Implementing Fire-and-Forget using ThreadPoolExecutor section.

Firstly, we create a ForkJoinPoolMalformedIdentityRepository that implements MalformedIdentityRepository interface to perform concurrency our task.

public class ForkJoinPoolMalformedIdentityRepository implements MalformedIdentityRepository {

private ExecutorService pool = Executors.newWorkStealingPool();

private MalformedIdentityRepository delegate;

public ForkJoinPoolMalformedIdentityRepository(MalformedIdentityRepository delegate) {

this.delegate = delegate;

}

@Override

public void addIdentity(Identity identity, String reason) {

pool.submit(() -> delegate.addIdentity(identity, reason));

}

@Override

public void addIdentity(InputStream message, String reason) {

pool.submit(() -> delegate.addIdentity(message, reason));

}

}

Secondly, we create an instance of ExecutorService by calling Executors.newWorkStealingPool(). Invoking it with no parameters will return a new ForkJoinPool with a concurrency level equal to the number of CPUs available to the JVM. While switching to ForkJoinPool may offer some performance benefits, the driving reasons for using it are nested concurrency, recursion, …

Introducing Threaded Recursion with ForkJoinPool and BlockingQueue

In this section, we continuously talk about ForkJoinPool. Like other classes that implement ExecutorService, ForkJoinPool can accept Runnable as a representation of the body of work, but the native representation of work for ForkJoinPool is the ForkJoinTask class. When a Runnable is passed into a ForkJoinPool, it’s adapted into a ForkJoinTask before being added to the queue. ForkJoinTask is the first class citizen in ForkJoinPool. A ForkJoinTask can be created in one of two ways, by extending RecursiveTask when the recursive segment as a return value, or extending RecursiveAction otherwise.

| If parallelizing … | … then extend … |

|---|---|

| recursion with results (E.g: sorting, searching) | RecursiveTask |

| recursion with no result (E.g. fire-and-forget) | RecursiveAction |

-

BlockingQueue

Queues are how these pools are able to do several tasks even when workers are not available. When a task is sent to a pool for execution, it’s added to a queue, then workers take tasks off the queue as they have cycles to do so.

BlockingQueue is one of the data structures in the Java Concurrency API that can be used to hold on to available tasks. This problem of adding and removing tasks to a queue reduces to the classic producer/consumer algorithm, and it may seem trivial at first glance, however if we elected to use the notify and wait primitives to accomplish our design, we would quickly be faced with classic difficulties of the correctly synchronizing access to the queue, and avoiding low-level pitfalls like waiting on a monitor outside of a loop.

BlockingQueue is a thread safe queue that removes these challenges by correctly synchronizing internally, and offering a full component of produce and consume methods that can block like take() method, or do not block like offer() method, or throw exceptions.

Implementing Fire-and-Forget using Thread Recursion

It’s similar some above section, we will go straight forward to our implementation that uses ThreadRecursion with MalformedIdentityRepository.

public class ProducerMalformedIdentityRepository implements MalformedIdentityRepository {

private MalformedIdentityRepository delegate;

private BlockingQueue<Runnable> todo = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>();

public ProducerMalformedIdentityRepository(MalformedIdentityRepository delegate) {

this.delegate = delegate;

// Typically, the consumer would be a separate process not under the control

// of this class. It is included here as an inner class for simplicity

new ForkJoinPool(4).execute(new Consumer());

}

@Override

public void addIdentity(Identity identity, String reason) {

todo.offer(() -> delegate.addIdentity(identity, reason));

}

@Override

public void addIdentity(InputStream message, String reason) {

todo.offer(() -> delegate.addIdentity(message, reason));

}

private class Consumer extends RecursiveAction {

@Override

protected void compute() {

try {

Runnable r = todo.take();

new Consumer().fork();

r.run();

} catch (InterruptedException ex) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

}

Wrapping up

- Understanding about the fire-and-forget pattern and how to apply solutions for improve the performance of system.

Refer: