When we are working with website development, especially doing something with form such as login, …, we have to be curious about how we can push data into the web server. What is something that help us to do these?

So, in this article, we will discuss about HTTP protocol to explain all of things that is relevant to our issues.

Table of contents

- Introduction to HTTP protocol

- Uniform Resource Locator - URL

- Uniform Resource Idenfifier - URI

- HTTP Request Message

- HTTP Response Message

- The brief conversation about how HTTP protocol works

- Wrapping up

Introduction to HTTP protocol

HTTP is abbreviation of Hypertext Transfer Protocol, and it is perhaps the most popular application protocol used in the Internet.

-

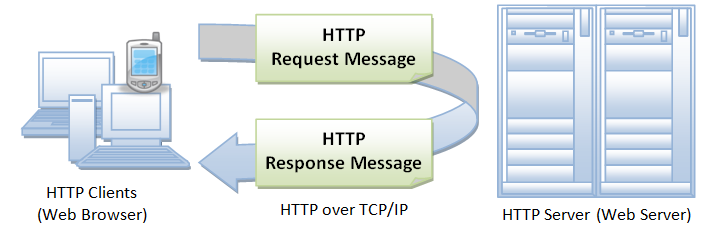

HTTP is an asymmetric request-response client-server protocol as illustrated. An HTTP client sends a request message to an HTTP server. The server, in turn, returns a response message. In other words, HTTP is a pull protocol, the client pulls information from the server (instead of server pushes information down to the client).

-

HTTP is a stateless protocol. In other words, the current request does not know what has been done in the previous requests.

-

HTTP permits negotiating of data type and representation, so as to allow systems to be built independently of the data being transferred.

-

Quoting from the RFC2616: “The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is an application-level protocol for distributed, collaborative, hypermedia information systems. It is a generic, stateless, protocol which can be used for many tasks beyond its use for hypertext, such as name servers and distributed object management systems, through extension of its request methods, error codes and headers.”

Uniform Resource Locator - URL

A URL is used to uniquely identify a resource over the web.

URL has the following syntax:

protocol://hostname:port/path-and-file-name

There are 4 parts in a URL:

- protocol: The application-level protocol used by the client and server. E.g: HTTP, FTP, and telnet.

- hostname: The DNS domain name (E.g: www.techmaster.vn) or IP address (E.g: 192.128.5.2) of the server.

- port: The TCP port number that the server is listening for incoming requests from the clients.

- path-and-file-name: The name and location of the requested resource, under the server document base directory.

For example:

In the URL [https://ducmanhphan.github.io/2019-02-05-HTTP-protocol], the communication protocol is HTTPS; the hostname is ducmanhphan.github.io.

The port number was not specified in the URL, and takes on the default number, which is TCP port 80 for HTTP.

The path and file name for the resource to be located is 2019-02-05-HTTP-protocol.

Encoded URL

URL can not contain special characters, such as blank or ‘~’. Special characters are encoded, in the form of %xx, where xx is the ASCII hex code.

For example, ‘~’ is encoded as %7e; ‘+’ is encoded as %2b. A blank can be encoded as %20 or ‘+’.

The URL after encoding is called encoded URL.

Uniform Resource Idenfifier - URI

URI is more general than URL, which can even locate a fragment within a resource.

The URI syntax for HTTP protocol is:

http://host:port/path?request-parameter#nameAnchor

- The request parameters, in the form of name=value pairs, are separated from the URL by a ‘?’. The name=value pairs are separated by a ‘&’.

- The #nameAnchor identifies a fragment within the HTML document, defined via the anchor tag <a name=”anchorName”>…</a>.

- URL rewriting for session management, e.g., “…;sessionID=xxxxxx”.

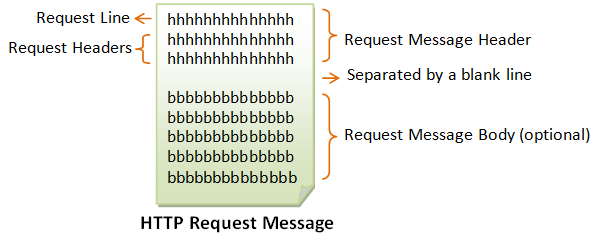

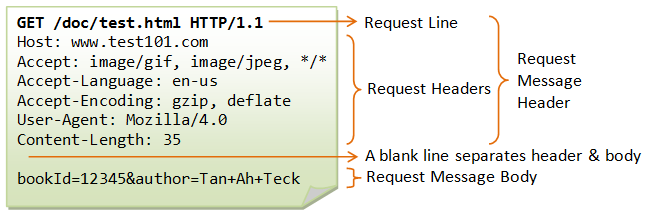

HTTP Request Message

The format of an HTTP request message is as follow:

-

Request Line

The first line of the header is called the request line, followed by optional request headers.

The request line has the following syntax:

request-method-name request-URI HTTP-version- request-method-name: HTTP protocol defines a set of request methods such as GET, POST, HEAD, and OPTIONS. The client can use one of these methods to send a request to the server.

- request-URI: specifies the resource requested.

- HTTP-version: two versions are currently in use HTTP/1.0 and HTTP/1.1.

For example:

GET /test.html HTTP/1.1 HEAD /query.html HTTP/1.0 POST /index.html HTTP/1.1 -

Request Headers

The request headers are in the form of name: value pairs. Multiple values, separated by commas, can be specified.

request-header-name: request-header-value1, request-header-value2, ...For example:

Host: www.xyz.com Connection: Keep-Alive Accept: image/gif, image/jpeg, */* Accept-Language: us-en, fr, cnIn HTTP/1.1, we will have some conditional request headers:

- If-Modified-Since (check for response status code “304 Not Modified”).

- If-Unmodified-Since

- If-Match

- If-None-Match

- If-Range

We will have some of the commonly-used request headers.

-

Host: domain-name - HTTP/1.1 supports virtual hosts. Multiple DNS names (e.g., www.nowhere123.com and www.nowhere456.com) can reside on the same physical server, with their own document root directories. Host header is mandatory in HTTP/1.1 to select one of the hosts.

The following headers can be used for content negotiation by the client to ask the server to deliver the preferred type of the document (in terms of the media type, e.g. JPEG vs. GIF, or language used e.g. English vs. French) if the server maintain multiple versions for the same document.

-

Accept: mime-type-1, mime-type-2, … - The client can use the Accept header to tell the server the MIME types it can handle and it prefers.

If the server has multiple versions of the document requested (e.g., an image in GIF and PNG, or a document in TXT and PDF), it can check this header to decide which version to deliver to the client.

(E.g., PNG is more advanced more GIF, but not all browser supports PNG.) This process is called content-type negotiation.

-

Accept-Language: language-1, language-2, … - The client can use the Accept-Language header to tell the server what languages it can handle or it prefers.

If the server has multiple versions of the requested document (e.g., in English, Chinese, French), it can check this header to decide which version to return. This process is called language negotiation.

-

Accept-Charset: Charset-1, Charset-2, … - For character set negotiation, the client can use this header to tell the server which character sets it can handle or it prefers. Examples of character sets are ISO-8859-1, ISO-8859-2, ISO-8859-5, BIG5, UCS2, UCS4, UTF8.

-

Accept-Encoding: encoding-method-1, encoding-method-2, … - The client can use this header to tell the server the type of encoding it supports. If the server has encoded (or compressed) version of the document requested, it can return an encoded version supported by the client. The server can also choose to encode the document before returning to the client to reduce the transmission time. The server must set the response header “Content-Encoding” to inform the client that the returned document is encoded. The common encoding methods are “x-gzip (.gz, .tgz)” and “x-compress (.Z)”.

-

Connection: Close Keep-Alive - The client can use this header to tell the server whether to close the connection after this request, or to keep the connection alive for another request. HTTP/1.1 uses persistent (keep-alive) connection by default. HTTP/1.0 closes the connection by default. -

Referer: referer-URL - The client can use this header to indicate the referrer of this request.

If you click a link from web page 1 to visit web page 2, web page 1 is the referrer for request to web page 2. All major browsers set this header, which can be used to track where the request comes from (for web advertising, or content customization).

Nonetheless, this header is not reliable and can be easily spoofed. Note that Referrer is misspelled as “Referer” (unfortunately, you have to follow too).

-

User-Agent: browser-type - Identify the type of browser used to make the request. Server can use this information to return different document depending on the type of browsers.

-

Content-Length: number-of-bytes - Used by POST request, to inform the server the length of the request body.

-

Content-Type: mime-type - Used by POST request, to inform the server the media type of the request body.

-

Cache-Control: no-cache|… - The client can use this header to specify how the pages are to be cached by proxy server.

“no-cache” requires proxy to obtain a fresh copy from the original server, even though a local cached copy is available.

(HTTP/1.0 server does not recognize “Cache-Control: no-cache”. Instead, it uses “Pragma: no-cache”. Included both request headers if you are not sure about the server’s version.)

-

Authorization: Used by the client to supply its credential (username/password) to access protected resources. (This header will be described in later chapter on authentication.)

-

Cookie: cookie-name-1=cookie-value-1, cookie-name-2=cookie-value-2, … - The client uses this header to return the cookie(s) back to the server, which was set by this server earlier for state management.

- If-Modified-Since: date - Tell the server to send the page only if it has been modified after the specific date.

For example:

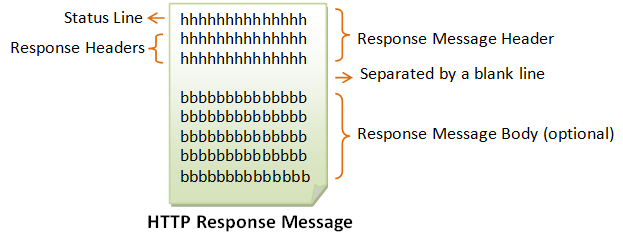

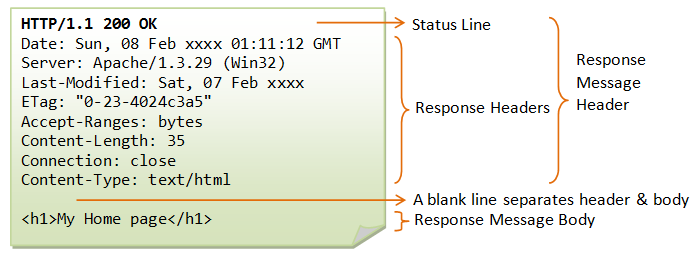

HTTP Response Message

The format of the HTTP response message is as follows:

-

Status Line

The first line is called the

status line, followed by optional response headers.The status line has the following syntax:

HTTP-version status-code reason-phrase- HTTP-version: The HTTP version used in this session. Either HTTP/1.0 and HTTP/1.1

- status-code: a 3-digit number generated by the server to reflect the outcome of the request.

- reason-phrase: gives a short explanation to the status code.

- Common status code and reason phrase are “200 OK”, “404 Not Found”, “403 Forbidden”, “500 Internal Server Error”.

For example:

``` HTTP/1.1 200 OK HTTP/1.0 404 Not Found HTTP/1.1 403 Forbidden ``` -

Response Headers

The response headers are in the form name: value pairs.

response-header-name: response-header-value1, response-header-value2, ...For example:

Content-Type: text/html Content-Length: 35 Connection: Keep-Alive Keep-Alive: timeout=15, max=100 -

Response Message Body

The response message body contains the resource data requested.

For example:

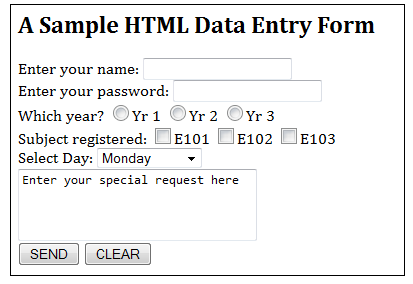

The brief conversation about how HTTP protocol works

In this part, we will describe how HTTP protocol works with POST method, in the form data.

In many Internet applications, such as e-commerce and search engine, the clients are required to submit additional information to the server (e.g., the name, address, the search keywords). Based on the data submitted, the server takes an appropriate action and produces a customized response.

The clients are usually presented with a form (produced using HTML <form> tag). Once they fill in the requested data and hit the submit button, the browser packs the form data and submits them to the server, using either a GET request or a POST request.

Each field has a name and can take on a specified value. Once the client fills in the fields and hits the submit button, the browser gathers each of the fields’ name and value, packed them into “name=value” pairs, and concatenates all the fields together using “&” as the field separator. This is known as a query string. It will send the query string to the server as part of the request.

name1=value1&name2=value2&name3=value3&...

Special characters are not allowed inside the query string. They must be replaced by a “%” followed by the ASCII code in Hex. E.g., “~” is replaced by “%7E”, “#” by “%23” and so on. Since blank is rather common, it can be replaced by either “%20” or “+” (the “+” character must be replaced by “%2B”). This replacement process is called URL-encoding, and the result is a URL-encoded query string. For example, suppose that there are 3 fields inside a form, with name/value of “name=Peter Lee”, “address=#123 Happy Ave” and “language=C++”, the URL-encoded query string is:

name=Peter+Lee&address=%23123+Happy+Ave&Language=C%2B%2B

The query string can be sent to the server using either HTTP GET or POST request method, which is specified in the <form>’s attribute “method”.

<form method="get|post" action="url">

If GET request method is used, the URL-encoded query string will be appended behind the request-URI after a “?” character, i.e.,

GET request-URI?query-string HTTP-version

(other optional request headers)

(blank line)

(optional request body)

Using GET request to send the query string has the following drawbacks:

- The amount of data you could append behind request-URI is limited. If this amount exceed a server-specific threshold, the server would return an error “414 Request URI too Large”.

- The URL-encoded query string would appear on the address box of the browser.

POST method overcomes these drawbacks. If POST request method is used, the query string will be sent in the body of the request message, where the amount is not limited. The request headers Content-Type and Content-Length are used to notify the server the type and the length of the query string. The query string will not appear on the browser’s address box.

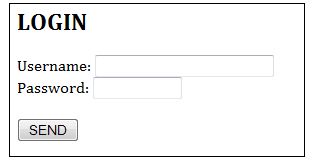

Consider that login form:

The HTTP GET request method is used to send the query string. Suppose the user enters “Peter Lee” as the username, “123456” as password; and clicks the submit button. The following GET request is:

GET /bin/login?user=Peter+Lee&pw=123456&action=login HTTP/1.1

Accept: image/gif, image/jpeg, */*

Referer: http://127.0.0.1:8000/login.html

Accept-Language: en-us

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.1)

Host: 127.0.0.1:8000

Connection: Keep-Alive

Note that although the password that you enter does not show on the screen, it is shown clearly in the address box of the browser. You should never use send your password without proper encryption.

http://127.0.0.1:8000/bin/login?user=Peter+Lee&pw=123456&action=login

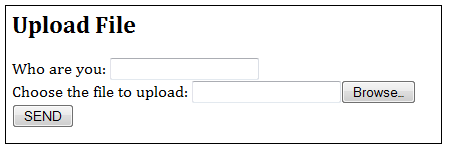

Consider the upload form:

with html:

<html>

<head><title>File Upload</title></head>

<body>

<h2>Upload File</h2>

<form method="post" enctype="multipart/form-data" action="servlet/UploadServlet">

Who are you: <input type="text" name="username" /><br />

Choose the file to upload:

<input type="file" name="fileID" /><br />

<input type="submit" value="SEND" />

</form>

</body>

</html>

When the browser encountered an <input> tag with attribute type=”file”, it displays a text box and a “browse…” button, to allow user to choose the file to be uploaded.

When the user clicks the submit button, the browser send the form data and the content of the selected file(s). The old encoding type “application/x-www-form-urlencoded” is inefficient for sending binary data and non-ASCII characters. A new media type multipart/form-data is used instead.

Each part identifies the input name within the original HTML form, and the content type if the media is known, or as **application/octet-stream otherwise.

The original local file name could be supplied as a “filename” parameter, or in the “Content-Disposition: form-data” header.

An example of the POST message for file upload is as follows:

POST /bin/upload HTTP/1.1

Host: test101

Accept: image/gif, image/jpeg, */*

Accept-Language: en-us

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=---------------------------7d41b838504d8

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 6.0; Windows NT 5.1)

Content-Length: 342

Connection: Keep-Alive

Cache-Control: no-cache

-----------------------------7d41b838504d8 Content-Disposition: form-data; name="username"

Peter Lee

-----------------------------7d41b838504d8 Content-Disposition: form-data; name="fileID"; filename="C:\temp.html" Content-Type: text/plain

<h1>Home page on main server</h1>

-----------------------------7d41b838504d8--

Wrapping up

- Remember HTTP Request message and HTTP Response message.

- Understand data in the form can be squeezed into HTTP protocol.

Thanks for your reading.

Refer:

https://www.ntu.edu.sg/home/ehchua/programming/webprogramming/HTTP_Basics.html#http_mesages

https://www.ntu.edu.sg/home/ehchua/programming/java/JavaServlets.html

https://www.ntu.edu.sg/home/ehchua/programming/java/JavaServletCaseStudy.html